Error handling in JavaScript

Errors can occur when executing programs, for example if a function is called with invalid arguments. As a developer, you should know how to react to errors within the program. A distinction is made between different types of errors:

Syntax errors

These occur when the syntactic rules of JavaScript are disregarded, for example if funaction is used instead of function in a function declaration or if the round brackets around the condition are omitted in an if statement.

funaction divide(x, y) {

return normalize(x) / normalize(y);

}

function normalize(x) {

return x <= 0 ? 2 : x;

}

Syntax errors are usually easy to find, as the interpreter points out the exact point of incorrect code. Syntax errors in JavaScript are only detected at runtime because it is an interpreted (and not a compiled) programming language. Depending on which development environment or editor is used, syntax errors are already pointed out during development.

Runtime errors

These are errors that only occur at runtime, i.e. when the program is executed. Strictly speaking, syntax errors are also runtime errors because they also only occur at runtime, but these are excluded here. Runtime errors are errors that would only occur at runtime, even in compiled programs. So syntax errors always occur when the faulty piece of code is interpreted. Runtime errors, on the other hand, only occur if the faulty piece of code is also executed, for example if variables that have not been declared are accessed within the program.

Complete Code - Examples/Part_94/main.js...

function divide(x, y) {

return normalized(x) / normalized(y);

}

function normalize(x) {

return x <= 0 ? 2 : x;

}

console.log(normalize(-2)); // output: 2

console.log(normalize(4)); // output: 4

console.log(divide(-2, 4)); // ReferenceError: normalized is not defined --> if normalize instead of normalized then output: 0.5

Here, within the function divide(), an attempt is made to call the method normalized() (misspelling actually normalize). If the entire code is loaded by the interpreter, there is still no error message, in contrast to syntax errors. Even the two calls to the function normailze() do not yet lead to an error. Only when the function divide() is called in the last line of the code, and thus also the non-existent function normalized(), does the program return an error message.

Runtime errors are more difficult to find than syntax errors because the corresponding faulty part of a program must also be executed. This is quickly tested for smaller programs. However, the more extensive a program is, the more difficult it is to find them. Source texts can be tested automatically with so-called unit tests, and unit tests can be a great help in finding such runtime errors.

Logical errors

Logical errors (also known as bugs) are errors that are caused by incorrect logic in the program. As a rule, such errors are caused by code that is actually intended to solve a specific problem but was implemented incorrectly by the developer. Such errors can also occur if something in the program behaves differently than expected, for example due to special features of a library.

Complete Code - Examples/Part_95/main.js...

function divide(x, y) {

return normalize(x) / normalize(y);

}

function normalize(x) {

return x < 0 ? 1 : x;

}

console.log(divide(4, -1)); // output: 4

console.log(divide(4, -2)); // output: 4

console.log(divide(4, 0)); // output: Infinity

A tiny logic error has been introduced here. The normalize() method now only returns a 1 for values less than 0, but no longer for values equal to 0. However, this bug is not noticeable with every call to the divide() function. The calls (divide(4, -1)) and (divide(4, -2)) work without problems because the second parameter is always assigned the value 1 and the result of the divide() function therefore remains valid. Only the call in the last line of the example produces an error or returns the value Infinity and is therefore incorrect.

Logical errors are the most difficult to find. These errors do not occur like runtime errors when the faulty part of the program is executed, but only if certain conditions are met. The so-called unit tests are also very helpful here.

1. Principle of error handling

Now that the error types are known, the question arises as to how they can be found. In the case of syntax errors, as already mentioned, it is relatively simple. Once the respective program part has been executed in the runtime environment, the error will show up there at the latest, but it is often already displayed in the development environment.

- In the development environment:

- In the browser during execution:

You can react to runtime errors with so-called error handling. If a runtime error occurs ("an error is thrown"), there are two ways in JavaScript (within browsers) to react to the respective error ("catch the error") and handle it. The error handling is also often called exception handling, as in software development the term "error" can alternatively be replaced with "exception".

The individual steps of error handling (error handling life cycle): 1. error occurs 2. error handling via try-catch 3. error handling via window.onerror (only in the browser) 4. error ends up with the user

First of all, you have the option of intercepting the error via so-called try-catch code blocks. If the error is not intercepted by such a try-catch code block, you still have the option of reacting to the error via the window.onerror event handler. This is only possible within browsers, as the window object is only available there. If the error is not responded to there either, it ends up with the user, i.e. the error is displayed on the console.

2. Catching and handling errors

First of all, error handling with try-catch code blocks. The try-catch code blocks get their name from the keywords.

try {

// Execute code that potentially produces errors

} catch (error) {

// Handling the error

}

The keyword try is used to introduce the code block that could throw potential errors. After the closing curly bracket, the keyword catch is used to define the code block that is to be executed if an error occurs. In the round brackets after the catch you define the name of the error object (the name can be freely chosen), which you can then access in the catch code block, like a kind of function parameter.

There are different types of errors in JavaScript, each of which is represented by a different object type. There are error types that JavaScript provides by default and there is also the option of creating your own error types.

Overview of the error types

| Error type | Description |

|---|---|

| Error | Basic type from which other error types are derived |

| EvalError | May occur if the eval() function is used incorrectly |

| RangeError | Occurs when a number is outside a range of values, e.g. when trying to create an array with a negative length new Array(-4) |

| ReferenceError | Occurs when an object is expected at a point, e.g. when trying to access a non-existent variable |

| SyntaxError | Occurs if an error is found in the syntax when parsing the source text with the eval() function |

| TypeError | Occurs when a variable or parameter is called with an invalid type |

| URIError | Occurs if an error has occurred in connection with a URI, e.g. if incorrect arguments are passed to the functions encodeURI() or decodeURI() |

Example:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_96/main.js...

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() {

const userInput = prompt('Please enter the length of the array');

const length = parseInt(userInput);

let array;

try {

array = createArray(length);

} catch (error) {

console.log(error.name); // output: RangeError

console.log(error.message); // Invalid array length

}

function createArray(length) {

return new Array(length);

}

});

The createArray() function expects the length of the array to be created as a parameter and passes this unfiltered to the array constructor. If a negative numerical value or an invalid numerical value is now entered, the array constructor (function createArray()) throws an error, which is intercepted by the try-catch block. The error object, which is available within the catch block via the error variable, provides two properties that can be used to obtain more precise information about the reason for the error:

| Property | Description |

|---|---|

| name | type of error |

| message | description of what failed |

3. Trigger error

To catch an error, this error must be triggered and thrown somewhere. In the example above, this happened via the standard JavaScript method. However, it is also possible to throw errors within a function itself. To do this, the throw keyword is used. The error object that represents the respective error is written after the throw keyword.

In the next example, an error is thrown within the checkAge() function if the argument passed is negative:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_97/main.js...

console.log(checkAge(19)); // true

console.log(checkAge(-19)); // Error: Age can not be negative

function checkAge(age) {

if (age < 0) {

throw new Error('Age can not be negative.');

} else {

return true;

}

}

If the interprter encounters an throw, it jumps out of the respective function. The subsequent statements in the function are therefore no longer executed.

The example can also be adapted, as the last statement (return true) would not be executed if the throw statement was executed beforehand.

Complete Code - Examples/Part_98/main.js...

console.log(checkAge(19)); // true

console.log(checkAge(-19)); // Error: Age can not be negative

function checkAge(age) {

if (age < 0) {

throw new Error('Age can not be negative.');

}

return true; // If an error occurs, this instruction is no longer executed.

}

Different errors can also be thrown at different points within a function:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_99/main.js...

console.log(checkAge(15)); // true

console.log(checkAge("Morty Sample")); // Error: Age must be a number

function checkAge(age) {

if(isNaN(parseFloat(age))) {

throw new Error('Age must be a number.');

} else if (age < 0) {

throw new Error('Age can not be negative.');

}

return true; // If an error occurs, this instruction is no longer executed.

}

Here, the checkAge() function has been extended by a test that checks whether the argument passed is a numerical value at all. If this is not the case, a (different) error is thrown.

The error that is thrown should ideally allow conclusions to be drawn about the type of error. The example could be adapted so that in the case of an incorrect type (no number although a number is expected) a TypeError is thrown and in the case of a negative numerical value a RangeError is thrown:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_100/main.js...

console.log(checkAge(15)); // true

console.log(checkAge("Morty Sample")); // TypeError: Age must be a number

function checkAge(age) {

if(isNaN(parseFloat(age))) {

throw new TypeError('Age must be a number.');

} else if (age < 0) {

throw new RangeError('Age can not be negative.');

}

return true; // If an error occurs, this instruction is no longer executed

}

If the function checkAge() is called several times with invalid arguments without bypassing the individual function calls with a try-catch block, only an error is output for the first function call with an invalid argument, as the following statements are no longer executed:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_101/main.js...

console.log(checkAge(15)); // true

console.log(checkAge("Morty Sample")); // TypeError: Age must be a number

console.log(checkAge(-15)); // Is not called

function checkAge(age) {

if(isNaN(parseFloat(age))) {

throw new TypeError('Age must be a number.');

} else if (age < 0) {

throw new RangeError('Age can not be negative.');

}

return true; // If an error occurs, this instruction is no longer executed

}

In order to be able to react to individual errors, the corresponding function calls must be surrounded by a try-catch block:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_102/main.js...

try {

console.log(checkAge(15)); // true

} catch(error) {

console.log(error); // Is not called

}

try {

console.log(checkAge("Morty Sample")); // No output

} catch(error) {

console.log(error); // TypeError: Age must be a number

}

try {

console.log(checkAge(-15)); // No output

} catch(error) {

console.log(error); // RangeError: Age can not be negative

}

function checkAge(age) {

if(isNaN(parseFloat(age))) {

throw new TypeError('Age must be a number.');

} else if (age < 0) {

throw new RangeError('Age can not be negative.');

}

return true; // If an error occurs, this instruction is no longer executed

}

A maximum of one catch can be used in each try-catch block.

4. Errors and the function call stack

If an error is thrown within a function, the interpreter jumps out of this function. If the error is not caught in the function to which the interpreter jumps, the interpreter also jumps out of this function. If the error is also not caught in the next function, the interpreter also jumps out of this function. This continues until the error is caught. If the error is not caught in any function and also not in the global code, the error ends up with the user. Errors should only be forwarded to the user if the user can do something with the error information and knows what to do to prevent the error from occurring again.

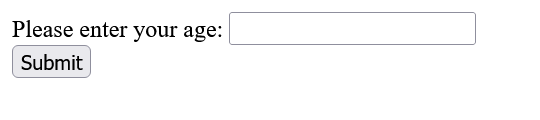

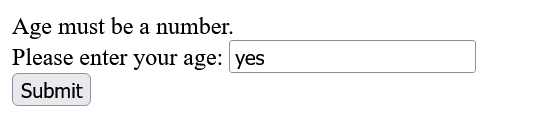

Example:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_103/main.js...

function checkAge(age) {

if(isNaN(parseFloat(age))) {

throw new TypeError('Age must be a number.');

} else if (age < 0) {

throw new RangeError('Age can not be negative.');

}

return true;

}

function enter() {

const age = document.getElementById('age').value;

try {

checkAge(age);

} catch (error) {

document.getElementById('message').textContent = error.message;

return;

}

}

Here the user should enter their age in the form field, if the information is incorrect (i.e. no number) the user is informed so that the error can be corrected by the user.

5. Calling certain instructions regardless of errors that have occurred

Sometimes it happens that, regardless of whether an error occurs or not, you want to execute special instructions after executing the faulty code. In this case, you can place another code block at the end of a try-catch block. This is introduced with the finally keyword, which contains exactly this instruction. All instructions contained in this finally block are executed in any case, regardless of whether an error occurs or not.

try {

// Run code that potentially produces errors

} catch (error) {

// Handling the error

} finally {

/* Everything that is written here is always executed,

regardless of whether an error has occurred or not. */

}

When the use of a finally block makes sense is best explained in practice. For example, if you want to access a database with JavaScript, this access usually consists of three steps:

- opening a database connection,

- the actual access (to data records, e.g. names, email, age of all users),

- closing the database connection.

These three steps are shown here in a simplified example program:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_104/main.js...

function openDatabaseConnection() {

console.log('Database connection open');

}

function closeDatabaseConnection() {

console.log('Database connection closed');

}

function getUsersByName(name) {

if(typeof name !== 'string') {

throw new TypeError('String expected');

}

/* ... */

}

function accessDatabase() {

openDatabaseConnection(); // 'Database connection open'

getUsersByName(19); // TypeError: String expected

closeDatabaseConnection(); // Not executed

}

accessDatabase();

Step 1 is represented by the function openDatabaseConnection(), step 2 by the function getUsersByName() and step 3 by the function closeDatabaseConnection(). The function accessDatabase() calls the three functions in this order. If an error occurs in the getUsersByName() function, such as an incorrect argument being passed here because there is no try-catch block, the error is passed on so that the closeDatabaseConnection() function is no longer called and the database connection is therefore no longer closed. In practice, if many errors occur, many such unclosed connections can also have an impact on the performance of a system.

This problem can be avoided by surrounding the call getUsersByName() with a try-catch block. There the error is handled within the function accessDatabase() and the following statements are executed:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_105/main.js...

...

function accessDatabase() {

openDatabaseConnection(); // 'Database connection open'

try {

getUsersByName(19);

} catch(error) {

console.error(error); // TypeError: String expected

}

closeDatabaseConnection(); // 'Database connection closed'

}

...

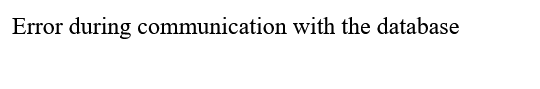

However, it can also happen that the error is handled within the accessDatabase() function, but an error should still be forwarded to the caller to inform them that something has gone wrong:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_106/main.js...

...

function accessDatabase() {

openDatabaseConnection(); // 'Database connection open'

try {

getUsersByName(19);

} catch(error) {

console.log(error); // TypeError: String expected

throw new DBError('Error during communication with the database');

}

closeDatabaseConnection(); // Not executed

}

function showUsers() {

try {

accessDatabase();

} catch(error) {

document.getElementById('message').textContent = error.message;

}

}

...

The customized example shows that the accessDatabase() function still calls the getUsersByName() function in a try-catch block and takes care of the error handling. To also inform the caller of such errors, a database error is thrown via the throw new DBError (error object DBError not real, only for illustration). The function showUsers() displays a corresponding user-friendly message to the user. The problem is that the function closeDatabaseConnection() is not executed in the event of an error, because the function accessDatabase() jumps out beforehand.

This problem can be counteracted by calling the closeDatabaseConnection() function in two places in the code. Once after the try-catch block and within the catch block before the new error is thrown. However, this has the disadvantage that the function call occurs in two places. In this example, in which only a single function call occurs twice, it is still tolerable. However, as soon as several instructions are to be executed in both cases, the code is correspondingly difficult to maintain:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_107/main.js...

...

function accessDatabase() {

openDatabaseConnection(); // 'Database connection open'

try {

getUsersByName(22);

} catch(error) {

console.log(error); // TypeError: String expected

closeDatabaseConnection(); // 'Database connection closed'

throw new DBError('Error during communication with the database');

}

closeDatabaseConnection(); // Not executed

}

...

It was not solved well here, as the code for closing the database connection appears in two places in the code.

And this is exactly where the finally block comes into play. This solves the problem in that the instructions contained in the finally block are executed in all cases before new errors are thrown within the corresponding catch block:

Complete Code - Examples/Part_108/main.js...

...

function accessDatabase() {

openDatabaseConnection(); // 'Database connection open'

try {

getUsersByName(22);

} catch(error) {

console.log(error); // TypeError: String expected

throw new DBError('Error during communication with the database');

} finally {

closeDatabaseConnection(); // 'Database connection closed'

}

}

...

There are three possibilities for try statements:

- Using try in combination with catch: Error-producing code is called, and any errors are caught.

- Using try in combination with finally: Error-producing code is executed, any errors are not caught, but in any case the statements in the finally block are executed.

- Using try in combination with catch and finally: Error-producing code is executed, any errors are caught, and in any case the instructions in the finally block are executed.